Food Sharing in the United States: What’s Changed During COVID-19?

Published by SHARECITY on the 26th June 2020.

Source: Beth Holliker.

Food Sharing in the United States:

What’s Changed During COVID-19?

By Lile Donohue

Hello to the SHARECITY community! My name is Lile Donohue and I am soon to be entering my final year at Trinity College Dublin, where I study Philosophy, Politics, Economics and Sociology. I’ve always had a personal interest in environmental and social issues, so being introduced to SHARECITY has been incredibly rewarding.

Over the last six weeks, I’ve been working with the SHARECITY Team to examine some of the impacts of the Novel Coronavirus COVID-19 on food sharing – some of which have already been documented in a previous SHARECITY blog post. I looked into the recent developments in community gardening, community kitchens and surplus food redistribution in the United States of America (USA), where I am currently based during the pandemic. The USA is an interesting case as it is currently the country with the highest number of COVID-19 cases. Living in the country during the COVID-19 pandemic also gave me helpful contextual information for the topic at hand.

Due to the need for a rapid review, I carried out a keyword search only on Google News which is a news aggregator app developed by Google. This wouldn’t pick up all the articles on the pandemic’s impact on food sharing and will likely under-represent insights from food sharing initiatives themselves who might document their activities on blogs and through other social media networks. However, it gives a good insight into media analyses. I found that, despite the global pandemic’s far-reaching negative impacts on nearly every aspect of our society, we are experiencing some unexpected opportunities for growth in these key areas.

On a hike in Big Basin Redwoods State Park in California, an hour and a half drive from my hometown.

Source: Personal Photography by Lile Donohue.

What’s happening in Community Gardens?

There was a noticeable abundance of articles about community gardens. The 23 points of data I evaluated for the key term ‘community gardens’ originated from 19 different US states. In over half of the articles I analysed about the topic, the community gardens in question were supported by the government. This is often in terms of community gardens having ‘meanwhile’ leases to use vacant state land until more permanent developments emerge. After being closed as a precautionary measure in many states at the outset of the pandemic, April and May 2020 saw many community gardens reopen as local officials recognised their importance in community life.

My research found that the number of growers in shared garden spaces is surging during the pandemic. Growers are adapting to the new social distancing measures and community gardens are proving to be a vital source of food and social connection. As people spend more time close to their homes due to “Shelter in Place” and “Stay Home” orders, it makes sense that the local, low-cost nature of community gardening is appealing. Community gardens enable people to undertake gentle exercise and interact with plants and soils as well. They resonate, as Prof. Anna Davies of SHARECITY recently argued, with every single spoke of the wheel of wellbeing.

Under the surface, however, is a more serious issue. According to a study published by Feeding America, a hunger relief organisation, COVID-19 is expected to increase the number of food-insecure individuals in the US by as much as 17 million (in 2018, 37 million Americans were already food-insecure). As unemployment skyrockets and the poverty rate follows suit, community gardens are part of the grassroots responses to meet urgent needs. Many of the reports I came across mentioned community gardens donating produce to community members in need, directly or through community kitchens. New initiatives are encouraging people to “not just grow [produce] for themselves, but to grow for others” (Pennsylvania Horticultural Society).

“The idea was always to give a resource to the locals in the form of land, tools, plants and education that folks could not afford on their own.”

– initiator of a community garden in Delaware (Rogers 2020).

A community garden in Brooklyn, New York on March 29th 2020 – it was closed at the time of this photograph due to COVID-19 restrictions.

Source: Steven Pisano.

Towerside Community Gardens in Minnesota on June 10th 2020.

Source: https://tinyurl.com/yd357aga.

What’s happening in Community Kitchens?

Community kitchens create opportunities for people to come together over food and can include anything from Real Junk Food’s ‘pay-as-you-feel’ restaurants to neighbourhood dinners for all, as offered by Open Table in Melbourne and Be Enriched in London. For this key term, 14 different states produced the 22 reports I evaluated. Only 4 of these were overtly government-backed, with mostly charities and non-profit organisations stepping forward to meet demand. Compared to community gardens, which in many cases can access state funding or use state-owned land, community kitchens seem to have always functioned relatively independent of the government, and this is no different during the pandemic. The valuable opportunities that these organisations are providing (to eat together with others or, under COVID-19 restrictions, delivering food to those who would normally avail of the community dinners) would likely benefit from a more centralised system with increased state support.

Community kitchens that were operating long before COVID-19 are experiencing a surge in demand, accommodating long-time service users as well as the millions of Americans who are experiencing food insecurity for the first time. In Santa Barbara, California, a soup kitchen has been serving nutritious soups to low-income residents and seniors with serious illnesses. To protect their clients’ health during the pandemic, the kitchen is operated by a closed circle of volunteers, with some cooks working fifteen hour shifts. Still, the volunteers remain dedicated: “Whatever the need is, we show up. You tell me and I’m there.” (DeVine 2020).

Commercial restaurants across the country are also undergoing a transformation into temporary community kitchens. In New York, award-winning chef and restaurateur Marcus Samuelsson has converted his restaurants into community kitchens through partnerships with food rescue non-profits. On the self-reflection that prompted him to make this choice, he says: “I always go back to what I know: Feed the people.” Through his multiple kitchens, he serves over 12,000 people every day (The Economist 2020).

This kind of business adaptation is keeping restaurant staff and farmers in work, feeding food-insecure communities, and reducing food waste. Many articles praised the provisional system for its community-centred goals. However, this is only a short-term emergency response. According to a report commissioned by the Independent Restaurant Coalition, 85% of independent restaurants, which comprise 70% of all restaurants, are expected to go out of business by the end of the year in 2020.

“We could have closed, or pivoted to takeout, but it was clear that the only real option was to continue to feed the community”

– Marcus Samuelsson, world-renowned chef (Samuelsson 2020).

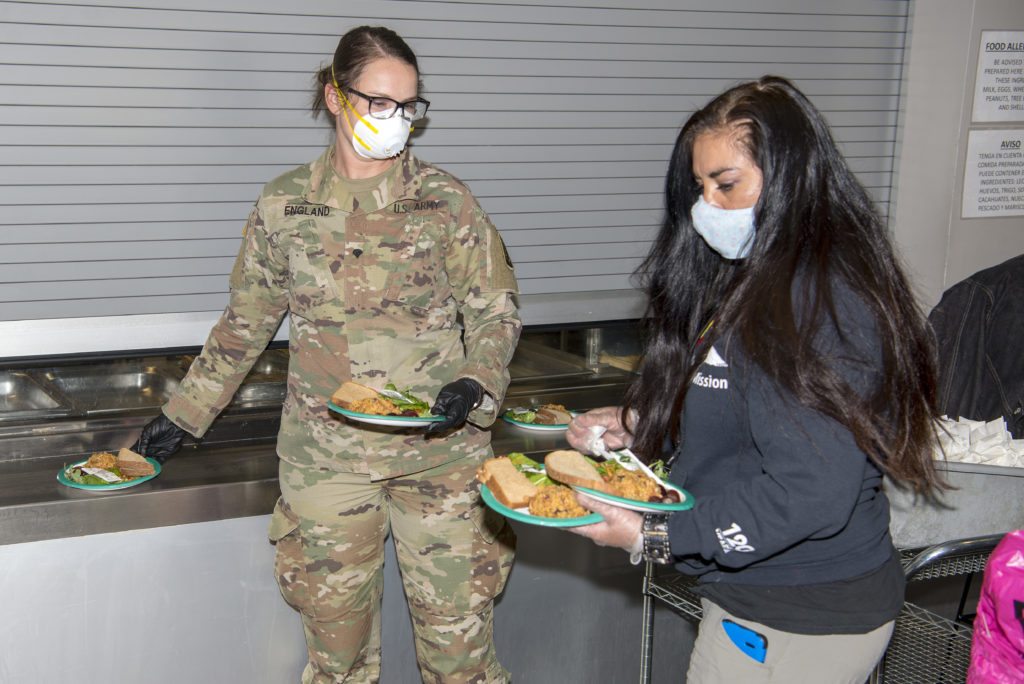

Colorado National Guard serving meals to guests without homes on April 9th 2020.

Source: John Rohrer.

What about Surplus Food Redistribution?

The redistribution of surplus food, often called food rescue in the USA, is used as a means to reduce edible food waste. Some of these activities have been documented by previous SHARECITY research in San Francisco. The 17 cases I analysed came from only 7 different states. Similar to community kitchens, food rescue is largely being carried out by non-profit groups.

While pre-COVID-19, the main focus of surplus food redistribution was to redirect surplus at the retail or consumer phase of the food system to reduce waste, the pandemic has made visible the fragility of the food system with food distribution networks under pressure. In some cases, farmers are destroying their crops and livestock because they can’t sell them as per usual.

At the same time the number of people facing hunger under the current COVID-19 climate is rising at an alarming rate. Billions of dollars in funding from the US government is being focused towards food rescue. However, critics find the process disorganised with resources not reaching the organisations and communities that need them. In response, many grassroots organisations, new and old are working overtime to ensure vital food supplies reach the people who need them most. While there are some positive developments in surplus food redistribution, such as the creation of new food rescue organisations, there is still work to be done. These efforts expose deep, pre-existing problems in the US food system. Dr. Jennifer Clapp, esteemed food security and sustainability academic, sums it up effectively:

“If the people who keep food supply chains moving are made vulnerable by unsafe working conditions, low wages and closed borders, the entire food system is vulnerable.”

(Clapp 2020).

The Delaware National Guard assisting at a food bank in Dover, Delaware.

Source: Brendan Mackie.

Final Thoughts

The COVID-19 pandemic and the societal responses to it has had many diverse impacts, some short term and others which will leave a longer impression on our everyday lives. In relation to food sharing there were initially government restrictions on access to community gardens, which are now slowly being relaxed under new socially distanced guidelines. We will need to wait and see whether new relationships with food, including many growing their own food, which started during the pandemic, continue as economies open up further.

Community kitchens and surplus food redistribution initiatives rallied to serve a growing proportion of communities in dire need of food and will continue to do so for as long as they can and for as long as a need exists. The fragility of the entire economic system, including the food system, has been revealed by COVID-19. Will this stimulate greater political will to address the root causes of the food system’s un-sustainability?

There are reasons to stay hopeful. Rethink Food Waste Through Economics and Data (ReFED), an organisation that analyses solutions for the problem of food waste, has been an active voice in this discussion. The Executive Director, Dana Gunders asks: “[…] In the long term, does it build more awareness? Do we actually find […] solutions that are created in this moment to last longer-term? Do we build habits that lead to lasting results? I think that’s where the opportunity lies” (Kaufman 2020).

Over the last few months, we have witnessed significant changes affecting food sharing, from the local level to the national in the United States of America. Issues like food insecurity or food waste aren’t new, but they have certainly become far more pressing. I hope we can maintain the heightened attention. After all, it’s in this state of emergency that we are implementing new solutions and strengthening food sharing networks.

Thank you,

Lile Donohue.

You can contact me at ldonohue@tcd.ie or find me on LinkedIn.

References

Clapp, J. 2020. “Spoiled Milk, Rotten Vegetables and a Very Broken Food System.” New York Times. Accessed at https://www.nytimes.com/2020/05/08/opinion/coronavirus-global-food-supply.html.

DeVine, B. 2020. “Organic Soup Kitchen Serving Community Throughout COVID-19 Crisis.” Keyt. Accessed at https://keyt.com/health/2020/05/07/organic-soup-kitchen-serving-community-throughout-covid-19-crisis/.

Kaufman, J. 2020. “As Food Waste and Insecurity Spike, ReFED’s COVID-19 Food Waste Solutions Fund Aims to Spark Change Beyond the Pandemic.” Foodtank. Accessed at https://foodtank.com/news/2020/05/as-food-waste-and-insecurity-spike-refeds-covid-19-food-waste-solutions-fund-aims-to-spark-change-beyond-the-pandemic/.

Rogers, T. 2020. “Milford Community Gardens Open.” Milford Live. Accessed at https://milfordlive.com/2020/05/31/milford-community-gardens-open/.

Samuelsson, M. 2020. “The Best Thing I Can Do For Harlem Right Now is Feed People.” Eater. Accessed at https://www.eater.com/2020/6/9/21285468/marcus-samuelsson-harlem-feeding-people-protests-pandemic.

The Economist, 2020. “The Economist Asks: Marcus Samuelsson.” Podcast. Accessed at https://www.economist.com/podcasts/2020/05/28/how-will-covid-19-change-the-way-we-eat.

© 2015 - 2024 ShareCity | Web Design Agency Webbiz.ie