Dublin’s Food Growing Scene: Are Community Gardens a Solution in our COVID-19 Future?

Published by SHARECITY on the 3rd June 2020.

Source: William Murphy

Dublin’s Food Growing Scene: Are Community Gardens a Solution in our COVID-19 Future?

By Alannah Owens

Vibrant community growing at micro-scales in Dublin, Ireland, could be the very thing that Local Authorities can and need to promote, in order to increase Dublin’s social resilience in a COVID-19 context.

Hello to the SHARECITY community! My name is Alannah Owens and I am a graduating Political Science and Geography Student at Trinity College Dublin, where SHARECITY is based. My degree has equipped me with tools to think about how we can tackle some of the starkest contemporary social and environmental issues facing society, including food sustainability. As SHARECITY has already undertaken great research examining the challenges and opportunities that food sharing initiatives face, and flagged the significance of the current pandemic for these same initiatives, in this post I’m going to throw other ideas into the mix specifically focusing on community gardening and the issues being raised by the current COVID-19 pandemic.

This past semester in 2020, I undertook a research project that investigated community gardens in Dublin. This blog reflects on my research and outlines how I became convinced that community gardens currently are, and could further become, an important social and food resource in Dublin, even at a time when communities must practice physical distancing.

Where all the ideas started – The Freeman Library, Museum Building, Trinity College Dublin.

Source: Alannah Owens Personal Photography

Community gardening in Dublin – What did I discover?

To undertake my research into community gardening in Dublin, I firstly used the listings and coordinates of all the community gardens recorded in the ‘Dublin Guide to Community Gardening’ (Moss, 2013) – the most up-to-date listing available at the time of research – to map past patterns of community gardens. I then created plans for future developments that would expand the impact of these gardens and also address issues of unevenness in the distribution of community gardens in Dublin.

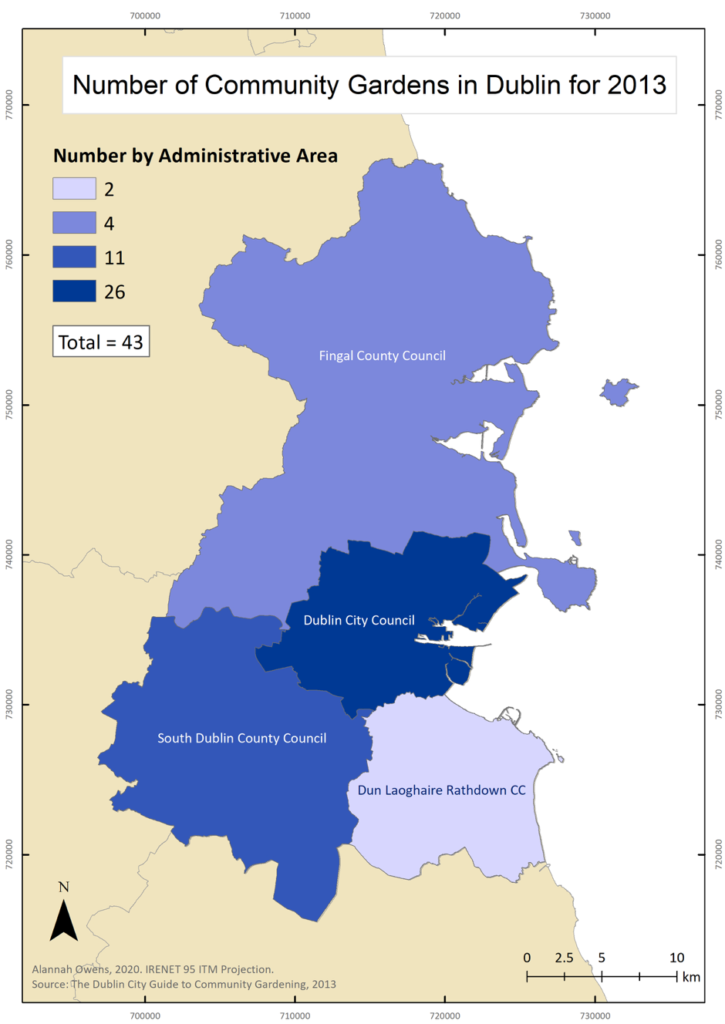

My conviction that Dublin had capacity for and could benefit from developing more community gardens only grew as I used Geographic Information Systems (GIS) to map the location of existing gardens and saw their uneven distribution and relative scarcity across the city of Dublin in 2013 (see Map 1 below). I found there were only 43 community gardens across Dublin, with Dun Laoghaire-Rathdown County Council area having the fewest by far (see Map 2).

Map 1 – Past distribution of community gardens in Dublin:

This figure shows the spread of Dublin’s community gardens in 2013 in terms of location (map on top) and quantity (map on bottom). Note the clustering of gardens around the city centre. The Dún Laoghaire–Rathdown County to the bottom right of the Dublin region has the fewest gardens of all the Dublin administrative areas.

Source: Alannah Owens 2020 GIS Mapping

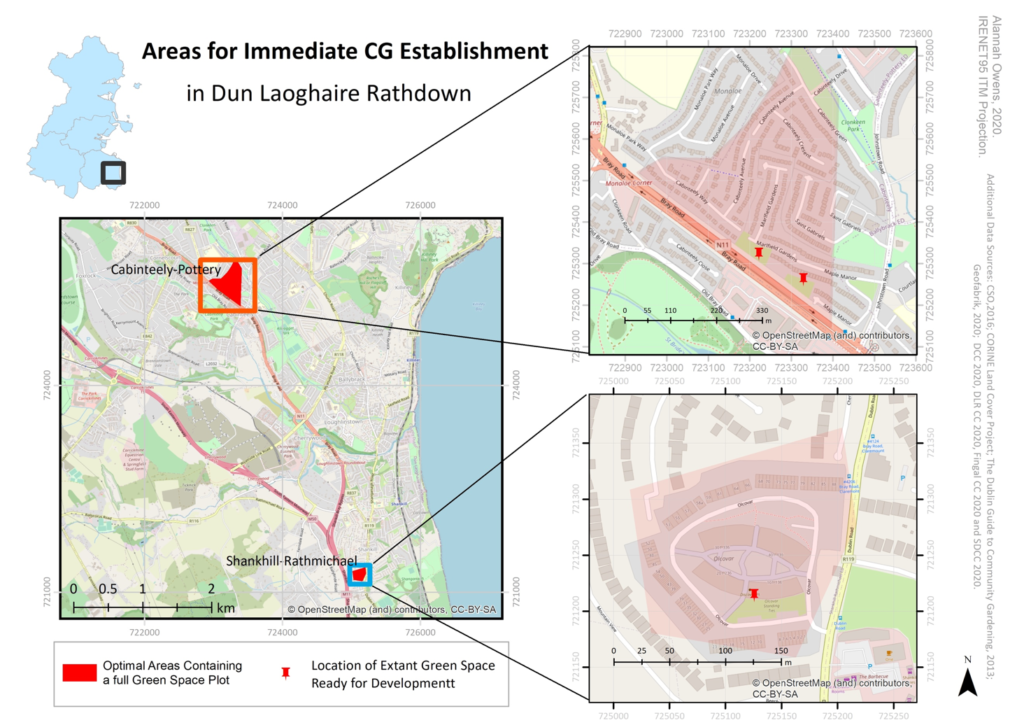

Using criteria that focused on increasing evenness in distribution and nearness to communities, my GIS mapping found there were many optimal areas for new gardens in Dublin, focusing on two sites ripe for immediate development in the Dun-Laoghaire Rathdown area. By building community gardens in this area that had the greatest scarcity in 2013, there would be a more balanced distribution (see Map 2 for the two specific sites recommended for development).

The parameters that I used to model future community gardens were that they be located in the heart of residential areas. I undertook this under recommendations from the Dublin Community Growers, that for the sake of accountability, surveillance, and maximum participation, community gardens be located where they will not be “out of sight (and thus) out of mind” (Moss, 2013, p 11).

To increase a community garden’s chance of success, it should ideally be visible from nearby houses and within easy walking distance for many people from their homes (Moss, 2013, p 6). Fields in Trust (2008) recommended the “240m straight line” figure as an appropriate benchmark distance for local landscaped areas to be accessible for children to play in. Of course this does not include all users, i.e. tourists or the elderly, however, I prioritised the accessibility needs of children in particular. This is because Dublin City Council (DCC) have observed that community gardens can be “efficient tools to educate schoolchildren and engage the interest of young people in particular” (DCC, 2016, p 165), and in line with that, this project proposes community gardens as sustainability education tools.

The gardens visible on the base maps for the two sites I selected in Map 2 – the Cabinteely-Pottery and Shankhill-Rathmichael sites – reflect these priorities. The gardens which could be developed on the green spaces marked by pins, are themselves surrounded by houses, and thus thoroughly embedded in the residential community.

Map 2 – Recommendations for future community gardens (CG) in Dublin: Sites selected were often existing green spaces and in the heart of residential communities.

Source: Alannah Owens 2020 GIS Mapping

COVID-19: What will this mean for community gardens in Dublin?

Under the COVID-19 pandemic in Dublin, government ‘lockdowns’ meant that several community gardens were not accessible to the general public. Due to this, an online petition started in Dublin to demand their re-opening, in a safe and manageable way. This petition highlighted the role that community gardens play in serving the needs of vulnerable people in the population who have been made even more vulnerable in terms of their mental health, physical health, food security and economic security.

This appears to have had some impact as in mid-May 2020, when the phased re-opening of activities in Ireland began, community gardens were one of the first amenities to re-open to the public, albeit with users required to follow careful safety guidelines.

More than just the re-opening of existing community gardens, the COVID-19 ‘Stay at Home’ restrictions could produce new opportunities for community gardens. As online gardening skills tutorials proliferate, now could be the time to engage people who may not have previously considered getting into community gardening. Despite schools being closed in Ireland, as in many other countries, COVID-19 may present a novel chance for increasing the food sustainability education of young people, as well as amongst the whole population.

Guidelines have been developed for community gardens in Ireland to comply with the current COVID-19 climate

Source: Community Gardens Ireland 2020

Where to Next?

It has become more apparent than ever before that green space, community gardens, and recreational parks are essential for the physical and mental health of our citizens in our cities, especially under the present COVID-19 pandemic.

Based on my GIS mapping research, and reflections on the world that has changed so much even since this final semester of my degree began a few short months ago, I think that there is great possibility for community gardens to serve as sustainable, resilience-enhancing tools.

I would advise Local Authorities who wish to help communities get back on their feet, to help communities embed small but widespread community gardens at the heart of residential areas. This will require resources (financial and otherwise), co-designed governance arrangements and training.

Perhaps being forced to hit the pause button on our hypermobile consumer society will allow us to re-think the quantity and quality of community gardens in urban centres, the ways in which they are planned and developed, and the supports that are provided for them from public, private and civil society arenas. This would ensure that they come to be considered essential parts of our urban fabric for the future.

Thank you, Alannah Owens,

Trinity College Dublin.

Email: alowens@tcd.ie

LinkedIn: www.linkedin.com/in/alannah-owens

References:

Dublin City Council – DCC (2016), Dublin City Development Plan: 2016-2022 Appendices, Dublin City Council, Dublin, accessed on 3 June 2020, Available at: http://www.dublincity.ie/main-menu-services-planning-city-development-plan/dublin-city-development-plan-2016-2022.

Fields in Trust (2008), Planning and Design for Outdoor Sport and Play, Fields in Trust, London.

Moss, R. (2013), The Dublin City Guide to Community Gardening, Dublin Community Forum, Dublin, accessed on 3 June 2020, Available at: http://dublincommunitygrowers.ie/resources-2/resources/.

An example of an existing locally embedded community gardening initiative in Brighton Square Residents’ Garden, Terenure, Dublin 6, Ireland.

Source: Alannah Owens Personal Photography

© 2015 - 2025 ShareCity | Web Design Agency Webbiz.ie