City Growers: Forsaken Lots to Productive Plots

Published by SHARECITY on the 17th October 2016.

City Growers: Forsaken lots to Productive Plots

A Conversation with City Growers Co-founder Margaret Connors.

By Marion Weymes

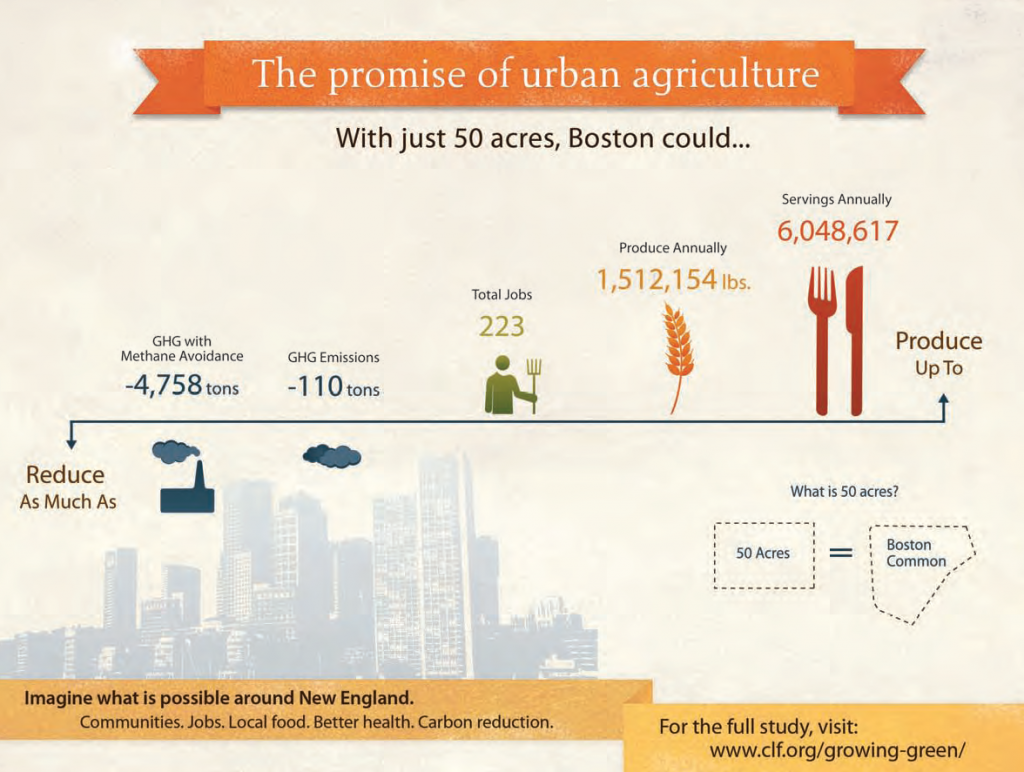

In the majority of cities around the world the price of land and housing is going up, at the same time that dwelling size and green space is going down. Yet many plots of urban land lie abandoned, ignored or discarded by developers, councils and communities, for years or even decades at a time. In Boston, a city of 700,000 people, it is estimated that 800 acres of land currently lie vacant. Last month Margaret Connors, a co-founder of the Boston based social enterprise City Growers, visited the SHARECITY team here in Dublin to discuss their experience accessing this land for intensive urban agriculture.

Established in 2012, City Growers works with community partners to secure land in the city for growing food and creating living wage green jobs, increasing agricultural production capacity, and improving food security and food access. However the transformation of vacant lots into productive farmland has not been easy, and City Growers have consistently faced an array of challenges as they attempt to build an economically and environmentally sustainable social enterprise.

Fundamental barriers to urban agriculture include urban land use and zoning policies, which have created landscapes in the US that are not supportive of urban food systems. Generally designed to accommodate and separate residential, commercial, and industrial uses, zoning has historically pushed agriculture out of cities, making safe, clean, and legal growing spaces increasingly scarce. The availability of urban land is critical for City Growers to continue to generate profit, grow sustainable jobs, and distribute local produce to businesses and community members, but unfortunately acquiring the right to farm on urban land means navigating a maze of red tape and regulation.

The regulation of urban agriculture is complicated by the fact that the concept remains poorly understood. Urban agriculture can be defined as the practice of cultivating, processing, and distributing food in or around a village, town, or city. Although widely practised across the world today, generating income and contributing towards food security for over 800 million people, it is fundamentally different from community gardens or allotments which generally only grow enough for personal or family consumption and have more widespread understanding and acceptance.

Yet urban agriculture can be particularly important in low-income urban areas, where it can help community members generate income whilst meeting their food needs. In Boston, 75% of vacant land (e.g. potential urban farms) is located in the three poorest neighbourhoods in the city, partly the result of systematic disinvestment through histories of red lining and discriminatory lending. The practice of urban agriculture has the potential to contribute to economic revitalization in these areas by creating local jobs and supporting local businesses.

Additional challenges for enterprises like City Growers lie in the soil itself, as much of the vacant land is polluted, containing lead and other toxins from old buildings, fires, and the illegal dumping of waste. Soil remediation is expensive, and it can take up to eight years for selected plants to take up heavy metals. This is time and money that urban growers can scarcely afford. Current solutions to this problem involve purchasing large quantities of clean soil and working in raised beds, although a more environmentally just approach might involve holding polluters accountable for the cost of soil remediation.

For Margaret, growing fruits and vegetables is about much more than just urban rejuvenation. Food is at the intersection of many pressing public health concerns, including obesity. City Growers hopes to make an impact by supplying fresh fruits and vegetables to local markets, restaurants and schools. In fact, one of the core visions of City Growers, and a big driver for Margaret’s involvement, is to work with schools to provide nutritionally dense and locally grown lunches. School meals are widely accepted to be of poor quality, as school authorities are forced to distribute food deemed suitable by the federal government with little say over its source, nutritional content, or ingredients. Somewhat counterintuitively, frozen food is often being moved thousands of miles across the country, irrespective of the fresh produce being grown just around the corner and the avoidable transport-related carbon emissions. At present, the most consistent and profitable recipients for City Growers produce are local restaurants, though diners are often unaware that their salad greens were sourced so nearby.

Ultimately, a realisation many like Margaret have come to is that for local food systems to flourish, the mechanics, philosophy, education and policy surrounding food will have to be fundamentally redesigned. As Margaret reminded us, it is ironic that as Michelle Obama works hard to visibly promote healthy eating, particularly in schools, her husband is signing off on legislation that continues to subsidize commodity crops such as corn whilst neglecting the importance of fresh produce and local supply chains. Without a huge overhaul, initiatives like City Growers will be consistently hindered by regulatory systems and infrastructures designed to support the growth of a federally subsidized industrial food system.

The landscape of urban planning and food policy is frustratingly slow to change, leaving many who are attempting to build sustainable communities and local food systems unsupported and forced to operate in a legal limbo. Governments at local and national levels are consistently playing catch up with progressive citizens, generally remaining content to ignore issues and look the other way until the level of public interest, and in some cases, lawbreaking, grow to a point that they are forced to legislate

However there is a parting in the clouds ahead for City Growers. An abandoned farm in Boston, with its original old barn still standing, is being restored by a community land trust that is working with City Growers to create an urban farming educational centre. City Growers now operates as a subsidiary of the social innovation non-profit The Urban Farming Institute of Boston, which supports urban agriculture in Massachusetts through education and training. Over the coming years City Growers aims to bring 20 acres of vacant land (made up of small ¼ to 1-acre lots) into food production the economy of scale essential for City Growers to become and remain profitable. Three acres is a start, but they are not quite out of the woods yet.

We wish City Growers and The Urban Farming Institute of Boston the best of luck, and look forward to following them on their journey.

Marion Weymes and Oona Morrow

© 2015 - 2025 ShareCity | Web Design Agency Webbiz.ie