SHARECITY SHARING CAFÉS

Published by SHARECITY on the 27th March 2018.

SHARECITY Sharing Cafés

In September and October the SHARECITY team ran two international co-design workshops inspired by the world café participatory mechanism. The first of these took place in Trinity College in Dublin, and the second at the European Roundtable for Sustainable Consumption and Production (ERSCP) on the beautiful island of Skiathos in Greece. With participants hailing from around the world the workshops brought together people from different backgrounds and with different experiences to talk about their encounters with food sharing, to brainstorm around the ways in which we might be able to identify the impacts of food sharing, and to think through what supports might be needed to help food sharing work towards sustainability.

Each workshop followed a similar structure. SHARECITY PI Anna Davies welcomed the participants and introduced the SHARECITY project and our interest in their experiences and insights. Brigida Marovelli then took up the reins and outlined the goals and structure of the workshop before dividing up the room into smaller groups, each with a facilitator to guide them through the questions.

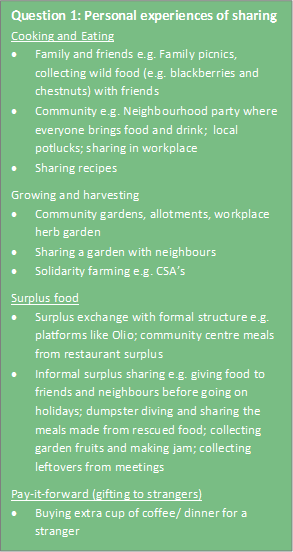

What are your personal experiences of sharing?

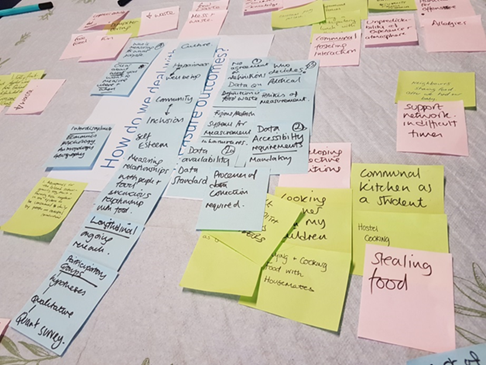

The first section of the workshop invited participants to discuss their personal experiences of sharing. The purpose of this exercise was to get people thinking about what it means to share food. Initially, the experiences offered were similar and familiar such as sharing meals at home with friends and family, but with a little help from the facilitators participants began to think more laterally about experiences surrounding food and what it means to share and experience food collectively.

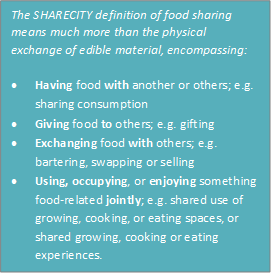

We asked whether they had borrowed gardening tools from a neighbour, or volunteered for a food donation programme; whether they had ever given their fridge contents to friends before going on holidays or used a community composter. Equipped with the expansive SHARECITY definition of food sharing participants were then able to provide a wealth of personal experiences for discussion, allowing for group reflections on the commonality and differences of these experiences. These were written on post-it notes and clustered by each group (according to e.g. what was shared, who was sharing, where did the sharing take place), setting up the tables for the next key question of the day.

What are the outcomes of sharing?

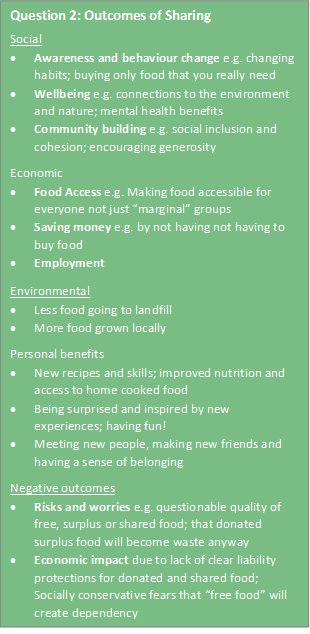

Leading on from the process of assembling experiences of food sharing participants were asked to think about the outcomes or consequences of these acts. We were interested in finding out what happened during or after these activities. How sharing made them, or others, feel, and what impacts did it have. These prompts led to overwhelmingly positive responses, ranging from personal feelings of happiness, inspiration, and social connection, to broader assumptions of improved food access, reduced food waste, and community building. However, as with any activity, less desirable outcomes can occur, and some tables ventured into deep discussions on trickier issues related to food sharing. Concerns were expressed over the quality of donated food, particularly surplus or ‘rescued’ food nearing use-by and best before dates, and ethical questions surrounding ‘free food’ and the long-term impacts of access to and dependency on food donations. Questions of dignity and choice were raised over acts of surplus food redistribution which could be seen as the dumping of one person’s ‘food waste’ onto people in need (or those who offer provision for them). There were concerns that donated surplus food may not lead to a reduction in food waste, but may perpetuate practices of over-purchasing if retailers and consumers feel they have a channel to dispose of it without putting it in the bin.

Leading on from the process of assembling experiences of food sharing participants were asked to think about the outcomes or consequences of these acts. We were interested in finding out what happened during or after these activities. How sharing made them, or others, feel, and what impacts did it have. These prompts led to overwhelmingly positive responses, ranging from personal feelings of happiness, inspiration, and social connection, to broader assumptions of improved food access, reduced food waste, and community building. However, as with any activity, less desirable outcomes can occur, and some tables ventured into deep discussions on trickier issues related to food sharing. Concerns were expressed over the quality of donated food, particularly surplus or ‘rescued’ food nearing use-by and best before dates, and ethical questions surrounding ‘free food’ and the long-term impacts of access to and dependency on food donations. Questions of dignity and choice were raised over acts of surplus food redistribution which could be seen as the dumping of one person’s ‘food waste’ onto people in need (or those who offer provision for them). There were concerns that donated surplus food may not lead to a reduction in food waste, but may perpetuate practices of over-purchasing if retailers and consumers feel they have a channel to dispose of it without putting it in the bin.

What emerged from the discussions was that many of these outcomes are not easily discerned, quantified, measured or even articulated. When participants were asked to identify the outcomes which were most difficult to capture, the non-physical and intangible aspects were quickly proposed. Whilst the material substance of food can be tracked, counted and weighed, how might we measure and record a feeling? What metric might reflect community spirit and how can we be sure of any direct causal relationship between the performance of sharing and improved health and well-being? The final question of the day focused on how we might approach these hard to measure outcomes.

How do we deal with these hard to measure outcomes?

Participants were invited to brainstorm potential means to address the hard to capture outcomes of sharing, with discussion ranging from familiar tools and approaches such as Bhutan’s Gross Happiness Index and existing psychological tools for measuring emotional well-being (e.g. mood diaries and mood metres), to the imagining of new (if unlikely!) methods such as the capacity to measure brainwaves. Despite the collection of tools and innovative ideas for future methods, there was consensus that measuring social outcomes posed a great challenge, particularly those which are essentially emotion-related, often fleeting and affected by multiple influences.

Longitudinal surveys were advocated by some participants as appropriate for addressing behaviour change, as well as determining increases in knowledge and skills. Identifying other forms of sharing that may spin-off from an act of food sharing, or related social enterprise or business ideas, may be used as an indicator of inspiration and social support. Other suggestions included adapting existing evaluation tools for food sharing activities such as those in use for tracking life outcomes following the release of people involved in prison gardening projects. However all of these require significant investment in systems of data collection and long-term reporting practices that may not be available to many sharing initiatives.

Moving away from the focus on individual moments of sharing within initiatives there were suggestions that broader assessments might take place by comparing places which have supportive structures for sharing food, such as the U.S. Bill Emerson Good Samaritan Law, with those that do not. Whilst not a direct impact of sharing activities themselves, these kinds of comparative practices may highlight some of the barriers and supports for food sharing activities.

Conclusion

Overall both workshops facilitated productive discussion and debate on a wide range of experiences, outcomes and rules associated with a variety of food sharing activities. We would like to take this opportunity to thank all the participants for their attendance in the workshops and for sharing with us their experiences, insights, ideas, and enthusiasm. As an embodiment of food sharing, we shared Greek Heirloom Tomato seeds with participants and we hope they will bear fruit and remind people of the practice and potential of food sharing.

The workshops provided an essential launching pad for the next phase of our research where we will face head-on the challenges of isolating the benefits of food sharing using a co-design process to develop a toolkit to better understand and communicate the sustainability impacts of food sharing activities and the initiatives that facilitate them.

Ultimately SHARECITY hopes to explore, not only what food sharing is, but how it can be supported to optimise sustainability benefits. We encourage any food sharing initiative who would be interested in testing a beta-version of our online sustainability toolkit later this year to get in touch at sharecity@tcd.ie.

Workshop Responses:

© 2015 - 2025 ShareCity | Web Design Agency Webbiz.ie