Co-creation models and Sharing in Seoul and Berlin

Published by Monika Rut on the 5th July 2016.

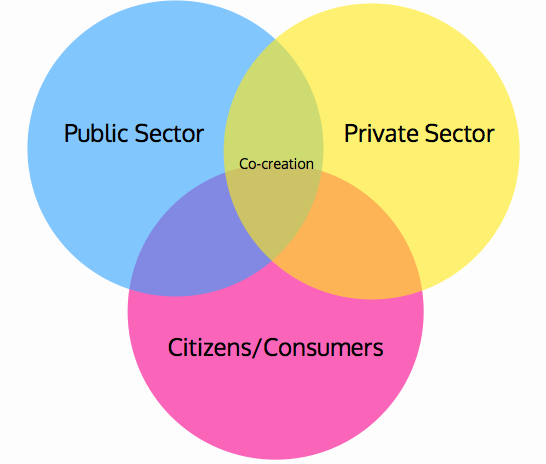

Since the economic downturn of 2008, there has been much made of emergent co-creation models and sharing in different sectors of society and economy in the media. Certainly, more businesses are looking for more socially responsible approaches to engage with new customers, and more public sector institutions are planning to promote more citizen involvement in urban commons and shared responsibility for the public good. This blog examines what these terms mean and how are they being operationalized.

Co-creation, as taken from its origins in business vocabulary, emphasizes a new form of engagement with customers in which they participate in the production of services and products. For example, for most of the companies that strongly rely on interactive user experience, the tool of co-creation is often implemented as a part of a wider customer-driven innovation strategy. On the other hand, in the case of public sector, the main intention and goal of co-creation are to encourage active participation and citizen’s involvement in policymaking decisions, which is based on a vision of shared ownership and socially valued outcome. In both cases, however, technology plays an important role of a connector between private sector, public sector and society at large that fosters interaction driven by a need of change.

If we look at how many cities worldwide are unable to cultivate sustainable food systems, co-creation techniques and practice of sharing seems to offer a solution in that regard while also being a part of an movement toward more sustainable cities.

For example, in smart megacities such as Seoul and Singapore, or aspiring ones like Taipei, the transition into fast paced urban lifestyles has brought about a loss of traditional agricultural practices. Along with this, the development of smart city ideals has increased social vulnerability. Infrastructures, such as urban edible gardens, urban agriculture, and micro and vertical farming, are helping foster self-sufficient food production and more communitarian sustainability projects. As models of sharing and co-creation in practice, they are critical to increasing economic and social resilience; developing what might be seen as a nurturing culture of sustainability.

In South Korea for example, agriculture activity has been dramatically reduced due to trade liberalization policies. Out of necessity to reconstruct fragmented local food systems, new forms of food sharing economies have re-emerged, which gave birth to consumer food cooperatives based on shared ownership and sustainable production and consumption patterns. Hansalim Food Cooperative, which is one of the most innovative and interesting consumers food cooperatives in South Korea, goes well beyond the limitations of the transactional exchange of just buying and selling by focusing on the importance of an interaction and exchange between different actors in the food supply chain.

Hansalim’s organizational structure supports the ideals of sharing through direct trade between farmers and consumers. Such trading also creates a culture of solidarity providing transparency of food supply chain, and supporting positive interplay between social innovations and technological innovations, which when implemented well results in system that minimizes food waste. As an example of how co-creation and sharing approaches has successfully re-claiming the right to food, Hansalim can be considered as being truly emblematic in its practice.

On the other hand, and in contrast to South Korea and Asian cities in general, the transfer of agricultural values to the urban landscape in some of the European cities such as Berlin have been more moderated. In Germany, for example, the tradition of urban food production has a long history. So-called “allotment gardens” were essential during the First and Second World War for food production, and in the last ten years similar models have demonstrated incredible potential to improve the quality of life and the city’s social fabric.

A more recent example, is the Berlin’s Freedom Templehof initiative resurrected out of a former US-airport, which quickly developed into a program for urban gardeners, involving more than 900 gardeners on the green field of 5000 m². As interest spread through the community to initiate the project, the Berlin municipality created a concept for shared ownership, allowing citizens to participate in the decision making process over the use of public land. Here, the co-creation model is manifested through joint effort of community driven initiatives with the aid of city management. Berlin’s Freedom Templehof is also indicative of a broader focus on participatory governance model, which is able to address the challenges of urban commons and city-based food system.

It is fascinating to see new forms of collaborations and new participation models emerging through co-creation approaches within urban contexts, set in motion by diverse actors from both business sectors as well as public, and citizens. By looking at the examples of co-creation in practice given above, we can see that in case example for South Korea, the Hansalim customer food cooperative truly focuses on the need of sustainable production and consumption patterns and certain sense of community connectedness; the Freedom Tempelhof project in Berlin addresses the role of citizen-driven activities in the framework of urban commons and inspires new form of participatory governance, which is designed with the principles of co-creation in mind.

Taken as a whole, we might wish to draw a conclusion that the rise of co-creation models and sharing practices has now reached a momentum that is driving all of us to a new political, social, economic and environmental practices. However we need more evidence than just a few hot spots on the map of world that can be rolled out in a way, which fundamentally transforms currently unsustainable urban food systems; SHARECITY hopes to contribute to this grand challenge.

Monika Rut

© 2015 - 2025 ShareCity | Web Design Agency Webbiz.ie